Onward, to the fun stuff. I've noted that both editing texts and studying them as historical, cultural, social, and of course physical objects are debated practices. But, thanks to my shameless, social network- sanctioned stalking, I came across this, the answer to it all: http://www.english.upenn.edu/~dwallace/europe/

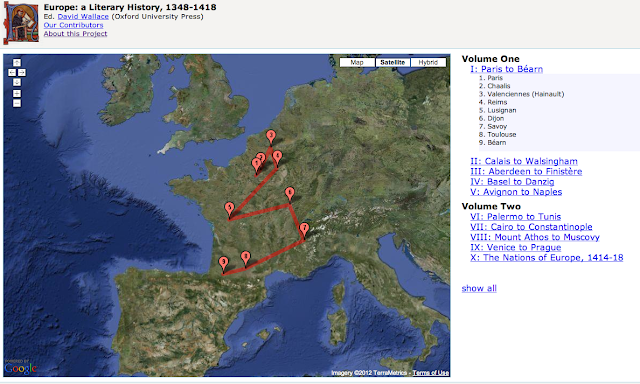

Its first sentences of "About this Project" anchor the work as relevant, responsible, and freaking genius: "This is the first literary history of medieval Europe to be attempted in English. Eschewing conventional, anachronistic organization by 'national blocks'-- English literature, French literature, etc.-- it considers literary activity in transnational sequences of interconnected places." Here is a perfectly accessible, interactive, digital project about book history in medieval Europe. Its commitment to fighting anachronistic impositions of scholars is as remarkable as its use of Google Earth; the satellite image reminds us of how removed we are from what we study-- the map, and the globe, of course, were much different then.

I particularly love that this is a group project. Collaboration addresses one issue that comes up in editorial and bibliographic treatises: the limitations of editor, or even the canon, as agents with agendas.

This site, of course, articulates this move: "Emphasis upon a multi-centered Europe draws us away from certain grand visions of a singular, pan-European culture developed in the twentieth century..."

Placing a timeline on a map (while keeping the linear index on the side) is a simple act, but one that makes all the difference. When you click on the flags, a write-up of that location's role in textual production pops up. You can read them each separately, or in order and in conversation with the others. The editors have made a choice, but allow you to make some, too.

I wonder, then, if this can be the next step in book production. I spoke briefly with a friend of mine, Will, about why digitalization hasn't really flourished in our fields--mine medieval, his Russian. He painted this awesome picture in my mind of some high school kid reading a Russian novel and being able to click on words, places, and names he didn't know. Once clicked, the link would connect you to a website, or at least a captioned image, of that unknown, and the reader could follow that link out of the book or return to it. Of course, this would be (and in some very limited cases so far, is) wildly helpful to readers of Old and Middle English. Don't know this word? No problem: here's the root and translation. Need some help with the declension? Click here. Can't this happen? Why isn't it?

In a world of digital everything, why are footnotes and other editorial moves the last to follow suit?

I'm wondering, too, if books could start looking like that map above. What would happen if we deconstructed works and mapped them out-- "Chapter 3 takes place here" so we could read them spatially, instead of just linearly? Could any editor get away with that, and at what cost?

Until next time, may your books' book-ness never be taken for granted.